SERBIA: LIVING TREASURES

Crafts and Trades in Serbia

PART 2 (Continuation from the previous page)

COOPERS’ TRADE

Coopers (in Serbian: pinteri, bačvari ili kačari) are craftsmen who make barrels, vats, flasks, etc. from wood of different dimensions. These items are used to store and transport food and beverages: wine, brandy, chimneys, relics, jams, cabbage, cheese, water, and even ash used to make soap.

Choice of wood depended on the content that will be stored in the cooperage product. For example, oak is mostly used for barrels in which wine will be stored. It is better to use mulberry for storing brandy, because over time, this drink gets a golden yellow color, so it has a better pass. Acacia and chestnut are also used to make barrel products, and ash, pine and spruce wood are often used for large tubs, in addition to oak. In any case, split and well-dried wood is needed. After the wood is cut down, and before use, it is dried for two, and in the case of high-quality barrels for wine and brandy, for three years.

Cooper Dušan Radovanović n his workshop in the village Striža, municipality of Paraćin (Central Serbia). PHOTO BY Maja Stošić

The cooperage craft is especially interesting because it combines several different techniques of wood processing: splitting, carving, bending and stacking, drilling and digging – when making barrels of large dimensions. There are two basic types of cooperage products – flat and rounded sides. In villages, various types of tubs are also made. Due to complexity of procedures, barrels of bent boards are made by master craftsmen. It was thought that one who knew how to make a barrel or barrel had passed the master’s exam for a cooper and would easily be able to make any other cooper’s product.

Demand for barrel products has declined in recent decades, due in part to cheaper plastic barrels and casks as well as new standards for food and beverage storage. However, producers of wine and brandy, as well as older cheeses, still prefer to use wooden barrel products. Wooden barrels and traditional wooden flasks can be bought at fairs throughout Serbia.

BLACKSMITHING

The blacksmith is a craftsman specializing in the processing of iron objects. Once upon a time, the blacksmith’s trade was one of the most appreciated – without it life in the countryside was unthinkable. Each village had its own blacksmith who produced variety of agricultural and other tools necessary for the rural household. Blacksmiths also made various weapons, such as swords and sabres. In the beginning, blacksmiths almost did not make decorative items, due to the relatively fast rusting of iron. Today, however, master blacksmiths mainly make wrought iron fences, furniture, mirror frames, candlesticks and other decorative items.

The main blacksmith’s tools are a hammer and anvil, and in addition to them, blacksmiths used a long blacksmith’s pliers, hammer, file, grindstone, punch, or chisel to make holes, clamps or blacksmith’s vise, iron saw, cutters, scissors for cutting sheet metal, bellows for fire control, as well as other necessary accessories.

Blacksmith Rade Aleksić in his workshop in the village Trešnjevica, municipality of Paraćin (Central Serbia). PHOTO BY Maja Stošić

The quality and beauty of the object itself depends on the skill of the blacksmith who makes it. As the blacksmith’s trade is very complex, it had to be studied for ten years. It is full of secrets in the art of making products that blacksmiths pass on from generation to generation. Some of the secrets relate to the mentioned way of preparing the mud, but also to the way of processing the items. Different uses of the object require different combinations of strength and resistance, and thus different ways of metal processing. Skilled blacksmiths can process the same piece of metal in several places in different ways. For example, the front part of the hammer is always harder than the back part, which makes it durable and strong.

In Slavic mythology god Svarog is a celestial blacksmith, creator of gods, the world and eternal fire. He forged the first wedding ring for his wife Vida and thus became the protector of marriage. He also taught people how to process steel.

Blacksmiths’ trade reached its peak at the beginning of 20th century, though demand for blacksmiths’ services lasted longer in rural areas. Nowadays, blacksmiths’ workshops are hard to find but the craft is not forgotten. Though many iron products are ready-made, available on industrial scale and some aesthetically acceptable, items forged in fire by skilled master-artists bear appealing uniqueness and originality.

COPPERSMITHS’ TRADE

Since 15th century copper utensils were widely used in both urban and rural areas throughout the Balkans. Due to their great durability these utensils were used for preparing food on open fire. In addition to being practical, copper utensils also had a decorative function in wealthy urban houses. Many copper items were richly decorated with engraving and ceasing techniques.

In the past, products were diverse: cauldrons, aranias and copperplants; then kitchen utensils (pots, pots, sahani, pans, pans, pans, blueberries, drinking water); hygiene utensils: small basins, barber basins, jugs, bowls; items for everyday use: braziers, coffee pots, coffee and sugar boxes, jugs; and sacral objects: discos, incense burners, goblets, baptistery pots. Since most of the items produced by the potters were dishes for eating and drinking, and copper is prone to oxidation, which creates a poisonous metal patina, these dishes had to be tinned, and tin was needed for that. Therefore, the coppersmiths were also engaged in tinning.

The most important in the potter’s workshop were the anvil, the fire-blowing bag, wooden and metal hammers, the potter’s pliers, files and scissors. Copper was supplied raw and melted in furnaces. Then several workers hauled him into boards with heavy hammers on the anvil. Then the process of making a certain item continued.

Coppersmith Mića Minić in his workshop in the village Riljac. PHOTO BY Maja Stošić

The masters of the potter had their interns and apprentices trained to become masters. The training lasted up to six years and was learned by the method of observation with participation. It was considered that the starting point for obtaining the status of a apprentice was to make at least 20 pans a day. Only after that, the apprentice could move on to making more complex products such as cauldrons, copper and turmeric, which were the basic knowledge and skills of journeymen.

The great centers of the coppersmits’ trade were the cities of Pirot, Niš and Prizren. There were also whole neighborhoods in which coppersmith’s shops dominated. Such shops still exist in Novi Sad, Belgrade, Valjevo, Niš, Leskovac and Vranje. Coppersmiths’ usually make cauldrons for roasting brandy, cauldrons for melting fat, sprinklers for vineyards and kettles for soup. Somewhat less often, they make pots and other copper furniture. Often, smaller coppersmith’s products are selling as souvenirs. Kazandžijsko sokače (Coppersmiths’ alley) in the city of Niš is today one of the tourist attractions of this city. Although today it is dominated by reastaurant and cafes serving traditional dishes and coffee made in copper coffee pots.

POTTERY TRADE

Pottery used to be the activity of women. Simple clay pots shaped by trampling pieces of clay and then baking them over an open fire are known as women’s pottery. The pots, called crepulje, were used for cooking and baking. The art of making crepulje is preserved in the Pirot region (south-eastern Serbia), for example in the village of Gostuša, a unique cultural and natural heritage site.

Men have become potters with the development of pottery wheels, hand-wheel and foot-wheel.

Working on a hand potter’s wheel, potters use one hand to turn the wheel and the other to shape the clay. Often, only one piece of calcite-saturated clay was most often used. As the synchronization of the hands was quite important, the pottery is quite simple in shape and usually without decoration. These pottery products were used for cooking and baking, but so did ceramics for heating houses.

Pottery made on a foot wheel was perfected throughout the Balkans on the basis of Byzantine traditions. The technology in which the foot moves the wheel, and the hands are free to shape the pots, has made it possible to pay more attention to decoration and colours – most often dark brown, yellow and green, rarely blue. Pottery made on the foot wheel is glazed, which endures lasting of colours.

Potter Dragan Antić, village Mali Suvodol, municipality of Pirot. PHOTO BY Aleksandar Ćirić

At the moment, traditional pottery made on a hand wheel in the village of Zlakusa (western Serbia near the town of Užice), is the only type of traditional pottery registered in the National Register of Intangible Cultural Heritage of the Republic of Serbia. The production process has three phases and includes: making, drying and burning pots in an open kiln. The specificity of this type of ceramics is the material from which it is made – a mixture of raw materials (clay and ground mineral calcite, in a specific proportion) obtained from this and nearby villages. The traditional forms of pottery from Zlakusa are dishes of different shapes and sizes (from 1 to 100 liters), which are mainly used for cooking and baking food. The pottery craft is passed down from generation to generation among male family members, who are the bearers of this knowledge.

KILIM-WEAVERS

Traditionally, kilim weaving is a female craft. The diligent hands of weavers create kilims, rugs and carpets of all sizes. There are three kilim-making traditions in Serbia. One was developed in the Vojvodina plain, the Bačka village of Stapar near the town of Sombor, while the other two kilim traditions were developed in typically livestock areas – Pešter plateau in south-western Serbia, and in the area of Stara Planina where the towns Pirot and Knjaževac became kilim-making centres.

Stapar carpet is made on wide horizontal looms, while in Sjenica – Pešter and Pirot kilim-makers weave on vertical looms. Beside weaving techniques, these three types of kilim-making traditions in Serbia differ in colour: white or beige tones predominate in Stapar carpet weaving, green colour is somewhat rarer, Sjenica-Pešter rugs are usually multicolour, while Pirot carpet weaving is dominated by red in several shades.

In Stapar carpet weaving, floral ornamentation predominates – roses, bouquets or garlands, while in Sjenica – cave carpet weaving, stripes (stripes) predominate over the entire surface of carpets. In Pirot kilim-making, figural elements are most often used, including lizards, birds, scorpions, stag beetles, turtles, doves, whereas the most common vegetal ornaments are: branched trees, roses, wreaths, etc. In older kilims, patterns are smaller and more harmoniously distributed, whereas the more recent pieces feature larger ornaments.

Kilim-weaver Maja Ćirić, village Gnjilan, municipality of Pirot (Eastern Serbia). PHOTO BY Aleksandar Ćirić

The girls in Pirot started learning weaving techniques at the age of twelve, first preparing the equipment that they brought to their husbands’ houses after marriage. Then they became professional kilim weavers, although the earnings were always small, inappropriate for the hard work of weaving kilims. Making kilim measuring half a square meter takes a month. Since it is done in one piece, in addition to a sharp eye, high concentration is necessary to correct mistakes immediately, especially when making kilims of larger dimensions. The carpet weavers do not make drafts, but work completely from the head, that is, after they sit down for the loom, so until the kilim is finished, they constantly have the idea of a story in front of their eyes, which they tell using ornaments. Each pattern is a symbol and each kilim is a story of joy or sorrow, love, motherhood and life’s destiny. Kilim-weavers often work together, sometimes singing, sometimes crying. Their inspiration makes kilim weaving a top art. As an object in use, the kilim lasts for 100 years – 50 years on one side and 50 years on the other. However, because of its beauty, it is considered a work of art, a family heritage.

SADDLERS AND LEATHER CRAFTS

The word sarach (also meaning saddler) is of Arabic origin and is used for a craftsman who makes leather objects. These craftsmen have been mentioned in historical materials in this area since the Middle Ages as ones making horse equipment, saddlebags, leather belts with bulkheads, leather holsters for small rifles or revolvers, leather bags, knitted claws and various decorative belts for horses. In addition to equipment for horses, in recent times, saddler also make other leather items: belts, bags, purses, wallets, glasses cases, bicycle saddles, and equipment for bikers, fans of motorcycles – modern “horses”.

Sarach shop smell like real quality leather. The process of processing and preparation of leather is divided into three phases, at the beginning the cooper performed them himself, then the leather was procured from tanners (vargi). From the middle of the 20th century, with the development of artificial and eco leather, saddler began to use these materials as well mainly to decorate various bags, belts, horse equipment and various holsters.

Leather craftsman Mirko Popović in his shop in Terazije Street, City of Belgrade. PHOTO BY Maja Stošić

Saddlers use following tools: sewing machine, various sledge knives, crescent-shaped knives, zumba-punches of different lengths and diameters, pliers long and wide, riveting pliers, awls, needles, wooden anvil, scissors, various raddles, various wooden irons, a barn counter and a barn called reslo. Also, these craftsmen had patterns that they used to tailor and decorate their products. Today, machines are used to sew leather up to 1.5 centimetres thick. However, thicker leather is still sewn by hand.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, the number of saddlers in Serbia decreased significantly. The main reason for this is the development of industrial production of leather. Today, there are only four sarach shops in Serbia: in Požarevac, Ruma, Kikinda and Užice. In addition to making items, these craftsmen also make all kinds of repairs of leather products.

From saddlers’ craft originate the craft of a purse makers known as “tashners” (tashna is Serbian for purse and small leather bags). They specialize in making bags, purses, wallets, various belts. Like saddlers, these craftsmen were initially using only natural leather, but today they also use artificial leather, which is cheaper, as well as many other materials, thus trying to adapt to the conditions dictated by the modern way of life. Although also slowly disappearing, tashner shops are somewhat more widespread than sarach shops, so for example, a handmade bags and purses made of natural or eco leather can be bought in Stara Pazova, and also in markets throughout Serbia.

BARBERS’ TRADE

Barbers were known in Vojvodina in the 18th century, while in Belgrade and the rest of Serbia they appeared from the 19th century.

As in the whole of Serbia in 1819 there was not a single graduated doctor, in addition to haircuts and shaving, barbers also performed medical work, dental and minor surgical interventions. By the 1880s, every barber had to learn how to extract teeth, bleed, perform skin defects, enemas, apply mustard herb, to know about first aid for suffocated, drowned, frozen people, and helping out in fixing broken bones of the arm or the leg. Emergency situations in which man finds himself to come to rescue were most often described as motivation for choosing barbers’ trade. Then they would become first inerns and then apprentices of master barbers. Training primarily consisted of watching and helping the master during work. In the second half of the 19th century, the obligatory taking of exams for simpler surgical services was introduced as a condition for taking the barber master’s exam before the commission of guild masters – barbers. Although at the end of 19th century exam for simpler surgical services was terminated, barbers continued to provide medical services. The older masters of the barber craft passed on their knowledge and experience to the younger generations, their interns and apprentices. As at the time the number of educated and trained MDs increased, barbers have worked very closely with doctors, in fact acting as physical assistants.

Barber Budimir Avramović in his shop in Vladike Nikolaja Street, town Paraćin (Central Serbia). PHOTO BY Maja Stošić

Barbers’ shops that simultaniously served to provide hairdo and shaving as well as small surgical procedures were up to the begining of 20th century rather simply decorated having a few chairs for performing services and a bench for those who are waiting. On the central wall hung a framed diploma on passing the master’s exam. A towel was hung on the door as a sign for a barber shop. At the begining of 20th century towel was replaced by a brass sheet and more attention was paid to interior design.

During the second half of the 20th century, barber shops in cities all over Serbia were replaced by hairdressing salons – women’s, men’s and unisex – which emphasized that their primary function was the hair care and styling. However, at the end of the first decade of the 21st century, barber shops – places where, in addition to cutting hair on the head, skilled craftsmen take care of the heads and faces of gentlemen – began to blossom again.

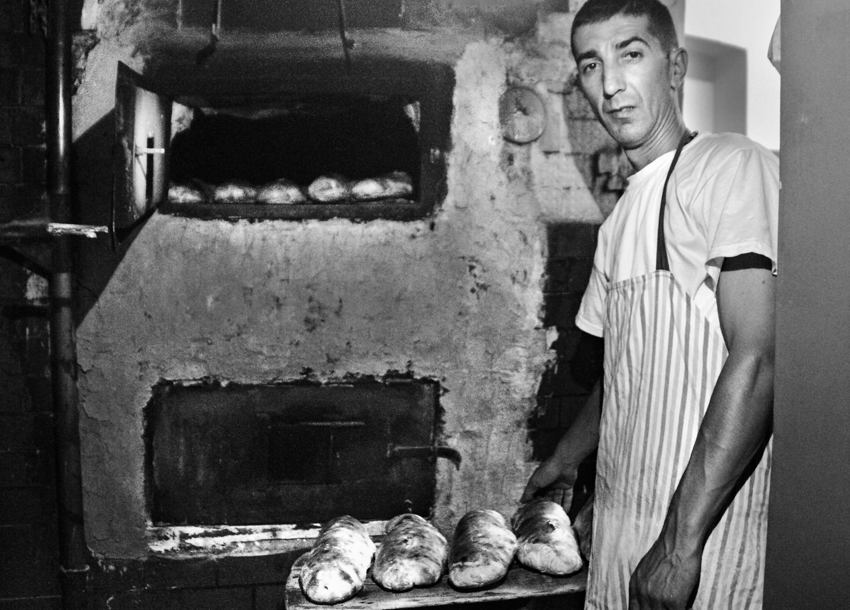

BAKERS’ TRADE

Bread plays important role in traditional Serbian culture. Guests are welcomed to the house by hosts offering bread and salt. Ceremonial breads are integral in religious customs. For example, slavski kolač – plain bread decorated by figures made of dough symbolising prosperity of the family – is integral in typically Serbian custom slava, celebration of holy patron of the family. Special bread called česnica is traditionally baked on Christmas.

Serbian soldiers in Balkans wars and 1st World War were getting highly nutritious whole-grain bread called tain.

Jovan Jovanović’s baker’s shop, Bajlonijeva Pijaca (Bajloni green market), City of Belgrade. PHOTO BY Maja Stošić

During Ottoman rule in towns bakers were mainly Turks called ekmedžije (from Turkish word for bakers), whereas Serbs were baking bread at their homes. Domestic bread was most often made of whole-grain wheat and it remained tradition for a long time after the liberation and formation of independent Serbian state. Following liberation from Turks in towns many Serbs were opening bakers’ shops. Unlike bread made in households, these bakers were making bread out of white flour. Beside bread, they were offering pies, cookies, pretzels, and other pastry. In 1894 in many Serbian towns bakers founded Bakers’ guild that was ensuring quality standards and proper qualification of bakers. If a person wanted to become a baker, firstly he’d become intern then apprentice and when master assess the knowledge and skills, he’d call guild to send a commission. Then a commission was testing the candidate and after he successfully pass the exam, guild was issuing Masters’ Letter, certificate that enabled new master to open his own shop or stay as a partner with his master.

After the 2nd World War, bakers’ trade became industrialized. Larger, factory-like companies were providing bread and pastries in towns and cities. Bakers’ guilds abolished in 1910 following the Law on shops was re-installed in mid-20th century as Serbian Bakers’ Union, still existing today.

In the last decades of the 20th century, the bakers’ trade flourished again. Nowadays, sweet smell of freshly baked bread and pastries comes from all over Serbian towns and cities.

Emisija je otvorena za sve muzičke događaje i ličnosti koje afirmišu izvorno muzičko stvaralaštvo. Ona okuplja istraživače, melografe, etnologe, etnomuzikologe i izvođače. Zaviruje u arhive i „muzejske eksponate”, oživljava legende, običaje, rituale – deo muzičke prošlosti koja i danas u tragovima živi u muzičkoj praksi pojedinih sredina. Prati promene varijanti izvornih pesama i njihovo putovanje kroz vreme.

Emisija je otvorena za sve muzičke događaje i ličnosti koje afirmišu izvorno muzičko stvaralaštvo. Ona okuplja istraživače, melografe, etnologe, etnomuzikologe i izvođače. Zaviruje u arhive i „muzejske eksponate”, oživljava legende, običaje, rituale – deo muzičke prošlosti koja i danas u tragovima živi u muzičkoj praksi pojedinih sredina. Prati promene varijanti izvornih pesama i njihovo putovanje kroz vreme.  Emisija je posvećena world music sceni, novitetima, trendovima, festivalima i novim albumima. U etru je od 2000. godine, a na Trećem programu Radio Beograda se emituje od 7. oktobra 2015. Emisiju uređuje i vodi poznavalac svetske muzike i organizator više festivala Bojan Đorđević.

Emisija je posvećena world music sceni, novitetima, trendovima, festivalima i novim albumima. U etru je od 2000. godine, a na Trećem programu Radio Beograda se emituje od 7. oktobra 2015. Emisiju uređuje i vodi poznavalac svetske muzike i organizator više festivala Bojan Đorđević.  Put svile, kao jedinstveno “radijsko putovanje”, do marta 2023. godine nedeljom je odvodilo slušaoce u neku od zemalja povezanih sa tradicionalnim Putem svile, uz aktuelna ostvarenja iz žanra “World music” i raritetne zapise tradicionalne muzike. Arhiva svih epizoda

Put svile, kao jedinstveno “radijsko putovanje”, do marta 2023. godine nedeljom je odvodilo slušaoce u neku od zemalja povezanih sa tradicionalnim Putem svile, uz aktuelna ostvarenja iz žanra “World music” i raritetne zapise tradicionalne muzike. Arhiva svih epizoda